Since April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month, we have been opening up dialogue on issues of sexual violence and how we can combat it as leaders.

Jean, Freely in Hope alumni, and Nikole, our International Director, have given insight into what survivor allyship looks like—without victim-blaming, throwing pity parties, or turning a blind eye, how can systems support the voices and dreams of survivors in our world?

When a survivor opens up to tell us their story, how should we respond?

Jean: It is very important to acknowledge your own reaction and emotions. It’s understandable to feel sad, angry, protective, or hurt, but be cautious in how you express it. If you are angry, just take a few minutes to process as the desire to fix the situation can be counterproductive. Even the storyteller’s body language is a great indicator of whether or not your response has been appropriate. Never feel pressured to respond, because you need to be comfortable in silence. It is the survivor’s right to share what they want, so they will appreciate it when you do not ask for specifics.

What is the difference between supporting a survivor who is a child and supporting an adult?

J: For a child, there is a need for safety. When I was thirteen I just needed to know that I was okay. When it happened again at twenty, I needed to know that it was not my fault. There is a wide spectrum of ages, experiences, and ways of coping; and each person has different needs.

“Justice might look totally different from one person to the next, so it’s important to put the needs of the survivor first.”

When you told me about your second experience with sexual violence, it was heartbreaking for me as a person, but also from an organizational perspective. My intention was to seek justice for you, but that’s not what you needed in that moment. What would’ve been more helpful for you?

J: Silence is such a safe space for people—just holding space for someone is important. There was so much guilt and shame directed that I directed toward myself because it had happened again. What I needed from you was to help me shift the blame from myself to the perpetrator instead of seeking justice. Justice might look totally different from one person to the next, so it’s important to put the needs of the survivor first.

Realizing that justice looks different for each individual is how justice goes from short-term support to long-term support. Short-term support could look like seeking justice for the perpetrator, while long-term support could look like providing opportunities that lead toward healing and transformation. What does this long-term support look like for you?

J: Healing goes far beyond providing an education. When you experience assault there is so much that shatters within you, and you find yourself starting over in all areas of your life. What was helpful for me was counseling, being transferred to a safe space, connecting with a circle of survivors, and being taught how God’s love was still present. Holistic care is needed because only catering to one part of a person’s needs is not enough. There is healing from both the spectrum of assault and the spectrum of shame, so the process may take longer than you expect. If you are unable to provide a survivor with adequate care, it is important to refer them to someone who is able to. Not doing so will only cause more harm.

As healing is a long-term journey, what are the elements that aid in the process?

J: There are so many phases and waves within the process of healing. As a caregiver, be sure to do your research, but also be careful to not immediately act by the book. When you offer help do not be a crutch to the person, but offer a space where they will become empowered themselves. You will never know the right things to say, but healing begins when the survivor finds their own voice.

You will never know the right things to say, but healing begins when the survivor finds their own voice.

How did you find your voice within that empowering, safe space?

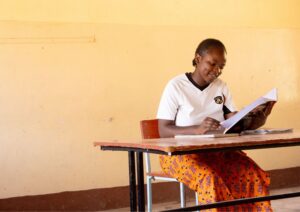

J: For me, singing and dancing in church was huge. As important as my education was, I needed to know that when I stood in front of people, I held power within my voice. Before, people would say that I danced to grab attention, but when FIH encouraged me to express myself by sharing my story, to sing and dance, it removed the shame from what made me who I am. I claimed my body through my dance and my voice through singing. As FIH became a safe space, I found my own creative space. I was able to move forward in every other aspect of my life. Creativity is where my soul resides, and the best place to begin healing.

Justice requires everyone’s full participation, otherwise it’s not true justice. How would you advise caregivers to respond in a situation where a survivor chooses not to continue receiving or utilizing the help that is offered?

J: It’s important to create a space where the survivor knows they will be welcomed if they decide to return to the community. Letting go is hard, but you cannot force someone to receive help.

How do you find balance between fighting for yourself and others fighting for you?

J: Trust that I will get to that point. When the second incident happened in my late teens, I was not ready to fight because of the perspective that I had of myself. I still blamed myself even though it wasn’t my fault. Trust that the survivor will eventually be ready to fight for themselves.

How do you show yourself grace when you find yourself retrogressing?

J: I still experience triggers at times, but singing and dancing helps me to let it out. I have to be comfortable with the fact that even though I am healing and progressing, I have not yet “arrived.” The same way I would not want someone else to criticize my journey, it is important to be my own ally.

It is important to have boundaries and practices for myself to prevent me from carrying the other person’s pain as my own. My purpose is to simply provide a space for them.

How can one control their triggers as a survivor, when supporting other survivors?

J: I have to enter spaces with other survivors knowing that I do not know all of the solutions and that I must listen and learn in order to help. As a survivor, I may be unable to handle certain stories, and therefore I may not be in the best place to offer help; referring a survivor to receive help from elsewhere does not make you a bad caregiver. It is important to have boundaries and practices for myself to prevent me from carrying the other person’s pain as my own. My purpose is to simply provide a space for them.

How do you support a survivor who is emotionally blackmailing because of their pain?

J: Some survivors are not in a space to make responsible decisions, and some may be very manipulative. While creating these relationships, be aware of the ways that people may cope or lash out, and be patient with them as well.

What was helpful (and not helpful) as far as the organization dealing with your family?

J: My mother is passionate about education, but she did not understand the reason for counseling. Coming from a faith background, it was important to incorporate faith in all that I was doing to show her that through counseling, FIH was not disregarding the faith aspect of my upbringing. Organizations need to include families in the journey and build trust by meeting them in a place that they understand, which for my family was education and faith. Also stay aware of different cultural perspectives, it may take a while but be open to listen and learn new things. When you understand that you are entering their space, they will be open to receiving what you have to offer.

What advice would you like to give to people who care for a survivor in their life?

This is a letter for caregivers:

Dear someone who cares, I am very afraid, I am afraid to let you in. I am unsure if you will stay after seeing all that unravels because of my circumstances. You might be too nervous to stay and I will have to start all over again. But do not give up on me because I am taking a long time to warm up to you. I just want to know that I can trust you with my story—that I can trust you with the fragile parts of me that comes with it. I know there is an outcome that you are expecting but please walk with me without them.

Teach boys to respect me too because boys will not always be boys, they are growing up into men who are disrespecting women. I am a girl growing into a woman, I am evolving.

Walk with me with the realization that there are layers to my brokenness. But if you make this space safe for me, all of my broken pieces will create something beautiful and you will witness the beauty of who I am.

Love,

Survivor

Jean’s passion for social justice stems from her personal experience of injustice and witnessing the same inequality across the globe. She holds an undergraduate degree in psychology and a minor in media studies. During her undergraduate studies, Jean volunteered at a juvenile facility and witnessed the gravity that broken systems have on the lives of the vulnerable. Her passion is exploring new policies which will help alleviate systems that perpetuate social injustice. She is currently interning with a United Nations affiliated organization and works with the United Nations Ecumenical Women Initiative in New York City. Her dream of working for the UN will allow her to continue her mission of empowering women to bring critical changes to society.

Nikole Lim is a speaker, educator, and consultant on leveraging dignity through the restorative art of storytelling. Nikole shifts paradigms on how stories are told by platforming voices of the oppressed—sharing stories of beauty arising out of seemingly broken situations. Her heart beats for young women whose voices are silenced by oppression and desires to see every person realize the transformative power of their own story. As our Founder and International Director, Nikole has been deeply transformed by the powerful, tenacious, and awe-inspiring examples of survivors. Their audacious dreams have informed her philosophy for a survivor-led approach to community transformation.